All he wanted to do was help his parents retire.

In fact, Martin never wanted to be involved with coffee at all. He fit squarely in the camp of kids who refused to follow in his family’s footsteps, who instead dreamed of pursuing a different passion and chasing his own conquests. But neither the mystical forces of ancestry nor the bond of family should be underestimated.

Childhood on a Coffee Farm

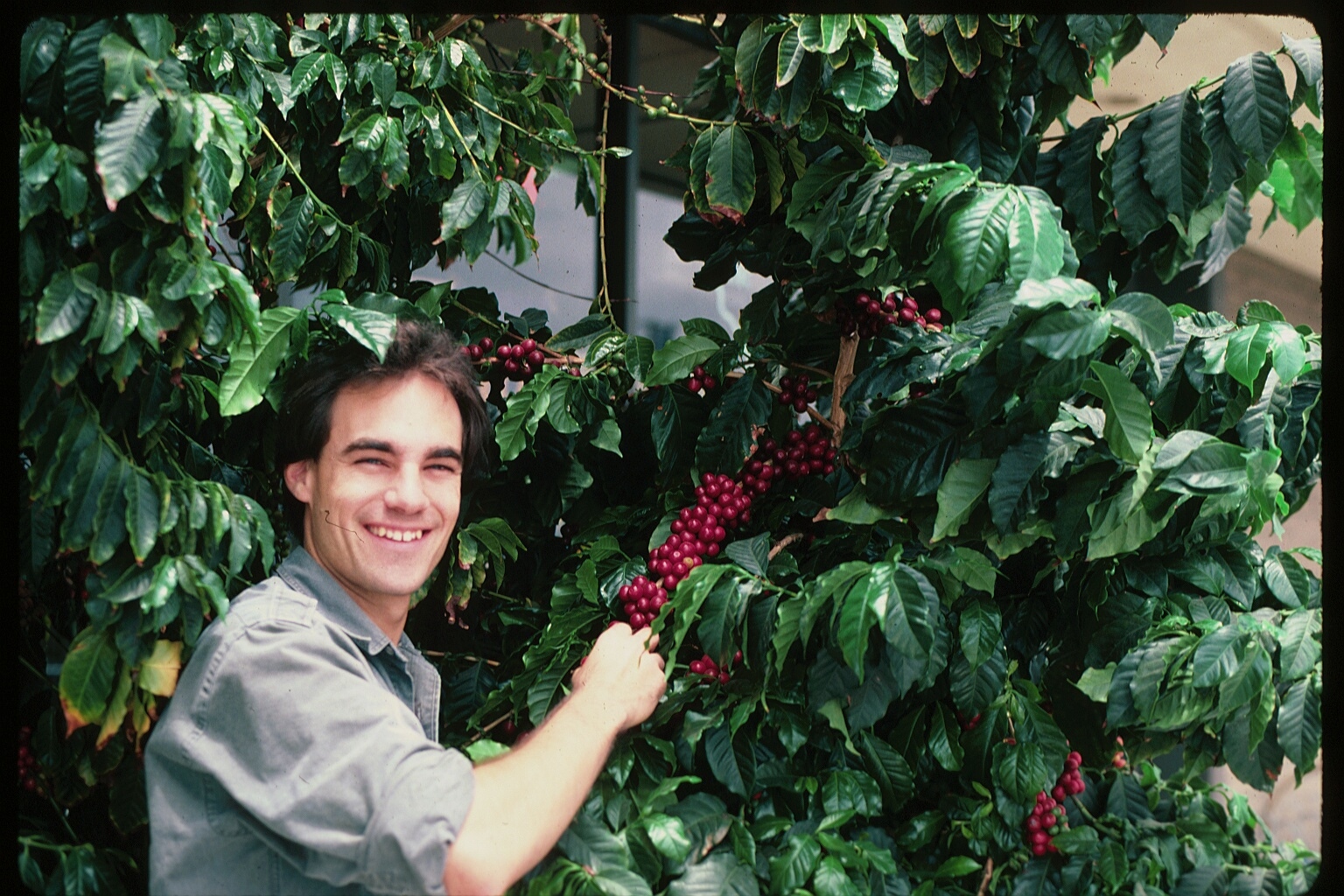

In his youth, Martin had little choice as to his life’s pursuit – he and his brothers grew up on a small coffee plantation in the highlands of Guatemala that his parents, Carl and Inga Diedrich, purchased in the 1960s. But the Diedrich family had been in the coffee trade for generations before that. Martin’s mother’s side of the family were coffee, tea and cocoa merchants in Germany for 160 years, and his dad’s family had been coffee growers in Costa Rica and Guatemala since 1916.

The Diedrich coffee farm was a rare breed – in the 1960s, most of the world’s coffee was commercial. But the Diedrichs grew rare and beautiful coffee varieties like Typica and Bourbon, and the farm was situated somewhere between the now-renowned coffee growing regions of Antigua and Chimaltenango. As Martin described it, the farm was surrounded by the most exotic and beautiful scenery in the world – “the towering volcanoes, the deep blue skies, the lush green vegetation, the cool temperate tropical mountain air.”

“We didn’t want to have anything to with coffee,” Martin said. “We had our own passions and desires, and it wasn’t going to be coffee, because coffee just represented really hard work. Who wants to do that for kicks?”

Forging his Own Path

When he was just 15 years old, Martin left the farm and his family to follow his true passion to become a Mayan archeologist, something he had dreamed about since he was nine years old. Martin began studying Mayan history and archeology at the University of Arizona and the University of Texas. He then launched his own jungle expedition guiding business, leading small groups of travelers to remote, ancient lost cities in the jungles of Central America. He was living his dream as the life of an Indiana Jones.

But in 1982, utter social, political and economic pandemonium hit Guatemala. The government carried out a campaign of genocide and terror against villages and communities in isolated areas. Amidst the chaos, a gang of thugs appropriated the Diedrich family’s land and farm, and the Diedrichs had no recourse to retrieve it. Martin’s parents had planned to retire on that farm, and suddenly it was lost.

With Carl and Inga’s safety net gone, and quickly approaching old age, Martin was faced with a difficult choice. He was a 24-year-old living his dream, and who had left his past life without plans to return to it. But with his whole life ahead of him, Martin decided to put a pause his prospering career to help his parents get back on their feet, thinking he would resume his adventures as a Mayan archeologist soon after.

“I felt like I was the missing man,” Martin said. “I needed to step in to help.”

The Beginnings of Diedrich Coffee

Martin endured hardship as well. He was working long hours in exchange for room and board from his parents, but no pay. But about a year into joining the family business, Martin was presented with an intriguing opportunity. The owner of a neighboring wine business, Harold Hanson, had plans to open a gourmet food center. Harold was one of the few people in Southern California familiar with coffee, gaining exposure to European espresso culture from his frequent travels to France. For his gourmet center, Harold planned to install a chocolatier, a deli, a kiosk for fine beers and Southern California’s largest wine cellar. And he offered to carve out space for a small coffee bar for Martin.

With his own location, Martin opened a prototype coffeehouse named in honor of his family: Diedrich Coffee. There were no other coffeehouses in existence to look to for inspiration, so Martin experimented with every element of the business. He purchased an espresso machine from the Pasquinis, the family with distribution rights for Cimbali. The coffeehouse concept was so foreign that even the Pasquinis, an Italian family in the coffee industry, didn’t know that a shot of espresso had to be calibrated, let alone how to calibrate a shot.

Martin’s first wave of customers was no better. They were so oblivious to coffee standards that they thought a cappuccino was an alcoholic beverage – they had only previously seen espresso machines in bars. Even the bartender was so puzzled by the contraption that they would concoct a drink so horrible that they’d add a shot of alcohol to render it drinkable.

A few years later in 1986, with all lessons learned on how to run a coffee bar, and with a better-informed base of customers, Martin opened his first full blown coffee house. Once it was up and running, it was an instant hit.

“I had lines out the door every day all day long,” Martin said. “Nobody else was doing anything like this, and America didn’t know about this. And they thought ‘wow, this is a cool idea.’ It caught on like wildfire.”

But beyond this feat, Martin had no other future goals for Diedrich Coffee. He had no intentions to expand the business or become wealthy from the endeavor. A runaway business success was far from anything he’d ever pondered.

“My family and I were all used to struggling to make ends meet,” Martin said. “I had no grand ideas about anything. We were simply just used to working very hard for every single penny and that’s all I knew how to do.”

Diedrich Coffee’s Rise and Fall

The period that followed was a trying time for Martin. He had given up 45% of Diedrich Coffee in exchange for $1 million to grow the company, and with that he lost much of the influence that comes with owning a business. A new CEO was brought in to oversee the company, a CPA with no experience in coffee or operating a multi-unit company. Martin was forced to surrender more of his company shares in a second equity dilution, and the investors decided to the take the company public in 1996.

Diedrich Coffee performed financially well for the first year of being a publicly traded corporation. The company acquired the specialty coffeehouse companies Gloria Jean’s, Coffee People and Coffee Plantation. By 2000, the company operated 500 locations in nine countries under four brands. It was the second largest coffee company in the world after Starbucks.

But Diedrich Coffee had skyrocketed to success without a solid foundation. The investors didn’t effectively manage the company’s expansion and took the financial support from underneath it. There was a revolving door of leadership with eight different CEOs in the eight years Martin was with Diedrich Coffee as a publicly traded company. Martin had to dilute his equity six separate times, and eventually owned just 3% of the stocks.

One day in June of 2004, Martin was blind-sided – he was told that the investors would not renew his employment contract at Diedrich Coffee. Martin was squeezed out of the company that he named after his own family.

“It was my entire identity at that point in life,” Martin said. “I had put 21 years into my heart and soul into it. Then in a matter of minutes, you’re out of there.”

Rebuilding with Kéan Coffee

“In the end, I have my health, my happiness, and I have the love of my wonderful family,” Martin said. “I have my skill, my craft, my ability to work hard and make sacrifice and rebuild myself. And I have my reputation in good standing here in my local community and in the coffee community worldwide. I have all of the things money can’t buy.”

Martin understood a key insight that the investors at Diedrich Coffee never grasped: that he was not in the coffee business, but the people business. He couldn’t define it when he was first establishing Diedrich Coffee, but his mission was to create a sense of community for his guests. When he first moved to Orange County in 1983, the only community gathering place was the local bar. But part of his motivation early on was that if there was no community, he would create it himself.

The same year he broke from Diedrich Coffee, Martin rebuilt a new coffeehouse and community gathering place with his wife, Karen. He didn’t want the new coffeehouse to be distracted by his past accomplishments. His purpose with the new venture would be to lift coffee to a new level of connoisseurship, and to represent the future. Which is why Martin and Karen named their new coffeehouse Kéan Coffee, after their son.

14 years after its inception, Kéan Coffee is a thriving business with two coffeehouse locations, a roastery and booming wholesale division. The business roasts a quarter of a million pounds of coffee per year just for its wholesale customers. As for their retail business – they have lines out the door every day. But more importantly for Martin, he and Karen feel deeply fulfilled in serving their local community with a welcoming gathering place for guests to connect with each other (you won’t find wifi inside the Kéan coffeehouses). And of course, they serve amazing coffee.

The Diedrich Family Legacy

“This is a way of life for me,” Martin said. “I get to apply the gift life gave me with coffee, having been born into coffee families, as much I thought as a kid and young man that I didn’t want to have anything to do with coffee. But I came back to the fold in my own time and own my way.”

Martin and Karen’s son Kéan is now 20 years, and like Martin when he was a young adult, he wants nothing to do with coffee. He is pursuing his own passion studying industrial design in college, and has his parents’ full support doing so. Martin isn’t urging him to get involved with coffee or to join the family business. But he said the option is open to Kéan if he ever wants to pursue coffee, and that Martin would be his guide.

But that’s for the future, and that’s for Kéan to decide.